2.4. The Shell#

Up until now we’ve been working in a graphical environment. This is good enough for regular desktop use, but if you want to do more interesting things (like programming robots!) you’ll have to be familiar with the shell, the text interface that everything else is built on. From now on, we will assume that you can find out how to do things with the GUI on your own, and concentrate on using the shell.

2.4.1. What is a “shell”?#

A shell allows a user to perform operations on the operating system, including starting and stopping programs, creating and deleting files and directories, managing user accounts, editing files, shutting down the computer, and much more.

Following the Unix philosophy, a shell program is at its core a quite simple: it waits for commands, executes these, collects the produced text output to show the user, and once all commands have finished it waits for the next command. Typically, the user types these commands. Alternatively, a sequence of commands can also be provided in a file called a shell script which can be executed by the shell in order without user intervention. We will explore these uses throughout this manual.

Nevertheless, as with Linux, there are many different shell programs available, many providing more advanced features such as colored text output,

command history management, and even word completion (to avoid typing long commands or file names).

The default shell in Ubuntu (and on many other distributions) is called bash, the Bourne again shell[1].

2.4.2. The prompt#

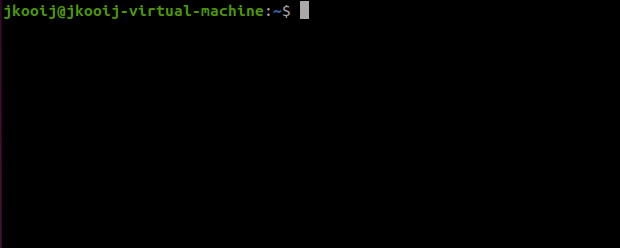

In the interactive mode, the shell displays a “prompt” every time it is ready to receive new user commands, as illustrated in Fig. 2.4. Behind the prompt a blinking cursor indicates the user can write their command. The command is completed once the user presses the Enter key, at which point the shell will try to execute the command.

A prompt can be configured to display useful information, such as the current logged in user, or the current date, or the working directory.

Some users prefer that the prompt is minimal, and shows no information except for a single symbol to indicate where user input is expected.

Typical symbols for the prompt include $ and >.

Configuring the prompt is a more advanced topic that we will not address now,

but be aware that you may find online documentation where the prompt is illustrated differently from your system’s default prompt.

Fig. 2.4 A shell displays a “prompt” when it is ready to receive new commands from the user.

The default prompt configuration of the bash shell in Ubuntu

shows the username (here jkooij), the name of the computer (here jkooij-virtual-machine),

and after a : the current working directory (~ indicates the home directory of the user).

Finally, this prompt ends with a $, which helps visually distinguish where the user can type their next command.#

Note

Throughout this manual we will not show detailed prompts as in the screenshot.

For simplicity, we will represent the prompt with just a simple $ as follows:

$

2.4.3. Terminals#

Since a shell is a basic program that listens to text commands and produces text output, the shell itself does not “know” about your screen, desktop environment, or even you keyboard. It relies on an external program to collect the user keyboard input, and show the produced output on the screen. Such a program is called a “terminal”, and (of course) Linux systems provide the use of many different terminal programs.

In the 1960s people had to talk to computers using paper punch cards; you would write your program, then create a stack of cards with small gaps in it in certain places and feed them to the computer. The computer would then do it’s job (if you didn’t make any errors) and spit out a number of punch cards containing the answer. You would then have to translate the gaps in the cards back to English. Of course, this makes it pretty hard to use your computer interactively. Therefore, terminals were invented. In the beginning, these were just keyboards. You could type one line of commands and enter it into the computer. Again, the computer would do it’s job, and spit out the answers on a line printer. Later, the line printer was replaced by a screen. You type your commands, the computer calculates and prints the answer on the screen.

Current Unix -based systems still use terminals at their basis to provide access to text-based interaction. However, we don’t need large screen-and-keyboards any more. Mostly, we use a program that acts as a terminal emulator, providing the user with a window to the system, similar to the original terminals. Nowadays, when we talk about “terminals” we usually simply refer to terminal emulators.

Within your desktop environment, you can open a terminal (emulator) just as any other GUI application. For example, you can search for the word “terminal” in the Start menu, or use a keyboard shortcut. There is usually a basic terminal program, which simply opens one shell.

Exercise 2.15

Open a terminal emulator in your desktop environment. This can be done using the “Applications” button in your desktop environment (Super-A, terminal, Enter), or even faster using a keyboard shortcut (Ctrl-Alt-t).

When you close a terminal, for example with the mouse by clicking the close bottom of the terminal window, it will also close the shell running inside it. It is also possible to tell the shell itself to stop, in which case the terminal will also shutdown because its connection to the shell is closed.

Exercise 2.16

Open a terminal, and make sure it is active (click inside the terminal, you should see a blinking solid cursor).

Type in the terminal the word exit and press Enter.

$ exit

This should stop the shell, and the corresponding terminal window should close automatically.

Exercise 2.17

Use the fast keyboard shortcut to open a new terminal.

This time to exit the shell, instead of typing exit and Enter, we can use an even faster keyboard shortcut.

Press Ctrl-D, the shell should terminate immediately even without needing to press Enter.

This character combination signifies to the shell that it has reached the “the end of input”, so it can shut down.

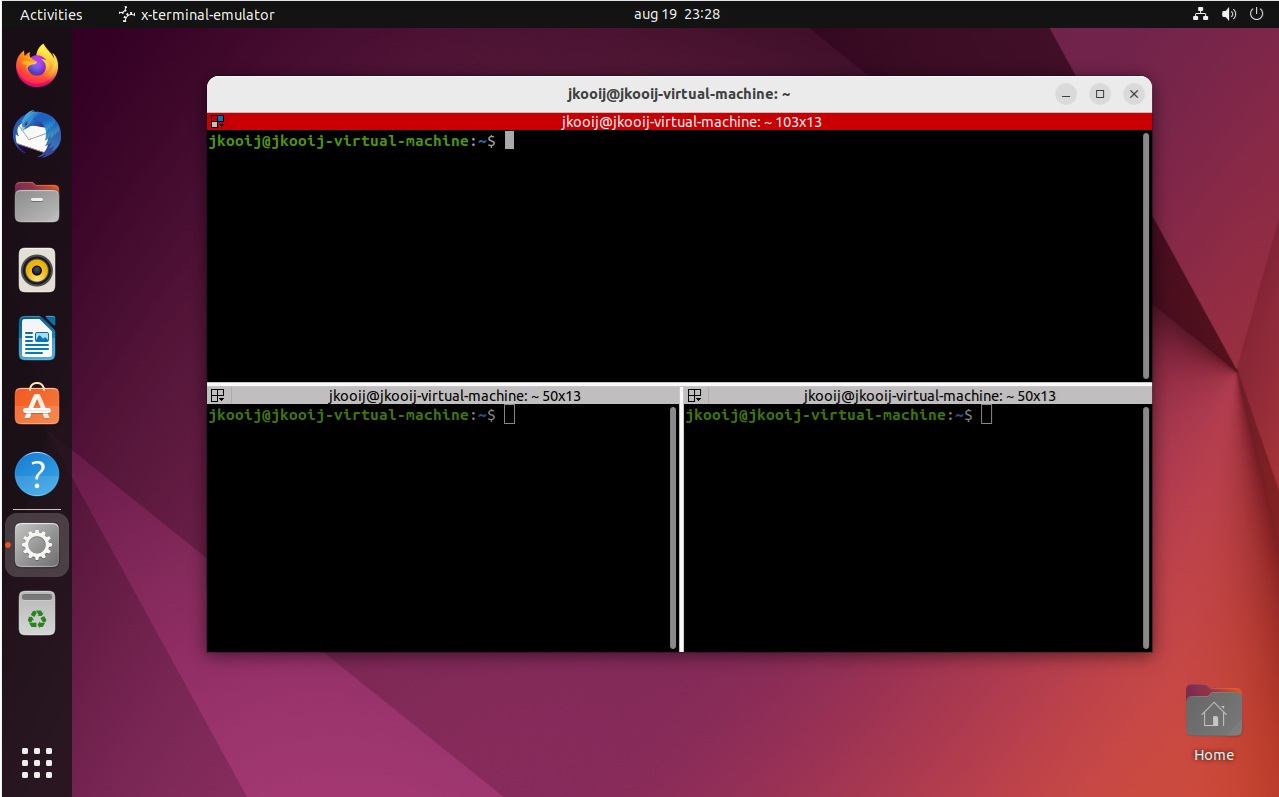

Once you become more proficient with working in the terminal, it is common to work with multiple open terminal simultaneously. One terminal might be used to edit configuration files of a system that you are developing, another terminal might be used to remotely login to a different computer over the network, a third terminal could be used to run test programs to see if your system is working properly. If you want to work with multiple shells simultaneously, you can simply start multiple basic terminal programs (the keyboard shortcuts to open and close terminals will become second nature). You could also use other terminal programs, which provide more advanced features to manage multiple shells. For example, the terminal program called Terminator has the capability to split its window into multiple shells side-by-side as shown in figure Fig. 2.5

Fig. 2.5 The terminal emulator Terminator allows to start multiple shells side-by-side. Here we can see it with three active shells.#

Exercise 2.18

If Terminator is installed on your system, open it. By default it just opens a single shell covering its complete window.

Recreate the horizontal and vertical split layout similar to Fig. 2.5. You can add a split by right-clicking inside the shell window with the right mouse button. Terminator should open a pop-up menu with different split options.

Finally, we note that on a Linux system you can also open several virtual terminals by pressing Ctrl-Alt-F1 through Ctrl-Alt-F6, which run separate from your desktop environment. Accessing these can be useful when you computer has problems and the GUI is not working properly anymore, for example when the harddrive is completely full which crashes most regular programs.

Exercise 2.19

Try opening one or more virtual terminals on your Linux installation. You will have to login with your username and password to use the terminal.

Figure out the following:

Which combination of Ctrl-Alt-F1 through Ctrl-Alt-F6 brings you back to your desktop environment?

If you switch away and then back to a terminal you logged into earlier, do you remain logged in, or has that terminal reset?